Tanishq Rupaal

Introduction

This blog is a primer of how basic GitHub collaboration works. This is not exhaustive of all features and tidbits but a basic explanation sheet to help people work on GitHub with relative comfort and ease.

GitHub allows you to host code with version control and the functionality to collaborate. Code is stored in a Repository where updates to the codebase are added as commits and feature sets are organized into branches.

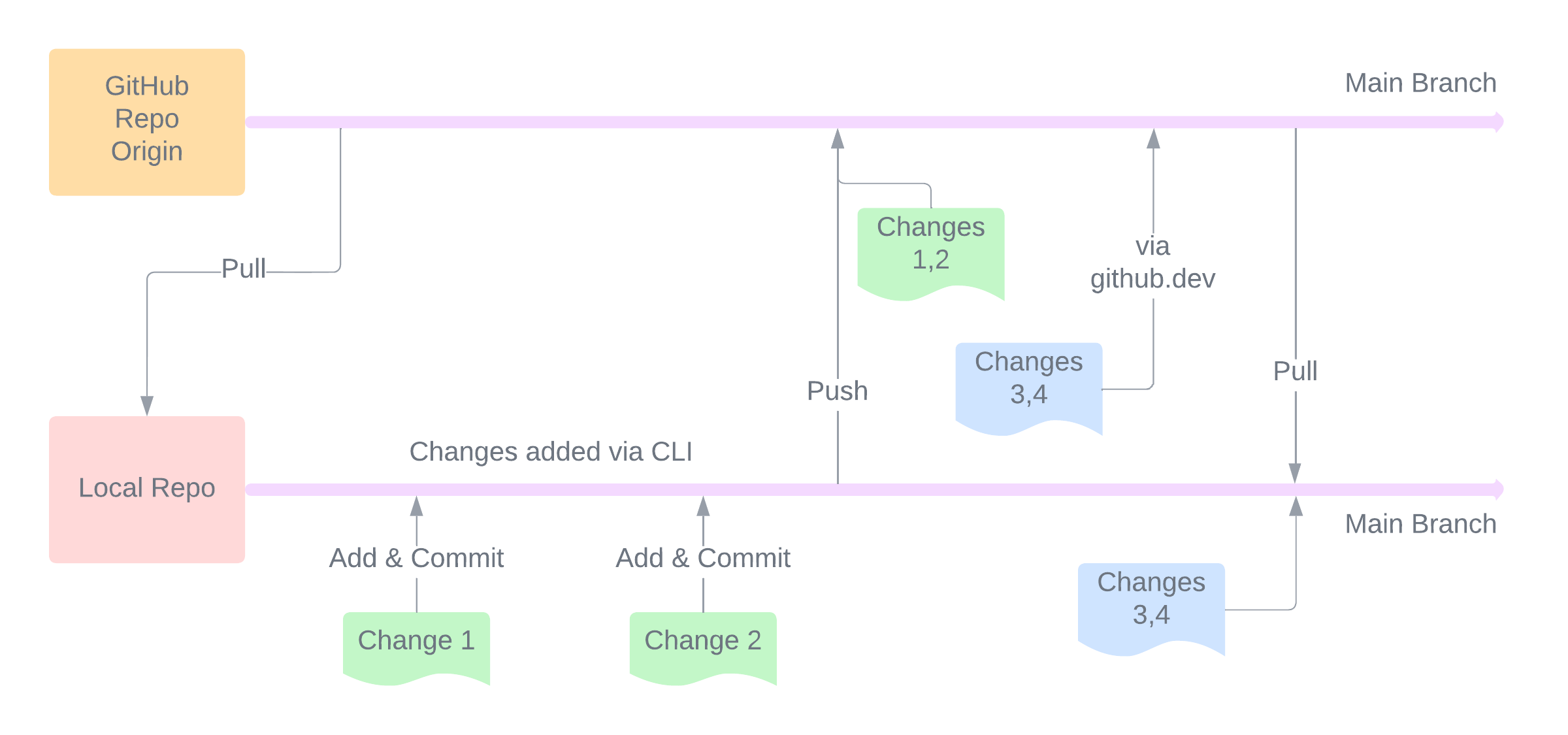

The image above shows a workflow cycle for a single repository. The repository storage on GitHub (github.com) is called origin. This code can be pulled down to a local workstation where changes are added and committed. The changes are then pushed to GitHub.

The browser version of GitHub allows launching a VS Code instance on the web by pressing . on the repository page. This launches it in github.dev which is a great place to make commits to code. New changes can be pushed to a branch by many people who have access to it. These can be pulled down to local workstations to work on the latest version of the code.

The same process can be replicated for branches other than main as well. The idea of branches is that you work on a feature set for your codebase in a branch say feature_x and when all changes are stable and working, the branch can be merged with the main branch, which is seen as a “final” place for code, so to say.

Working on a GitHub Repository

General Workflow

- A repository can be cloned to a local machine using →

git clone [repository link] - A look at current status i.e., files

stagedfor commits, current changes, etc. →git status - Add changed files to be committed →

git add [file_list]or add the entire directory usinggit add . - Commit currently added changes with a message →

git commit -m "[description]" - Push all local commits to origin →

git pushorgit push origin main - Pull changes from origin →

git pullorgit pull origin master - To check the log of commits so far in a repository →

git logorgit log -n 5to limit to 5 latest commits - To reset the local clone to the last commit and discard all changes →

git reset --hard(! this can discard hard work so be careful)

Similar operations can be done via the GUI or GitHub Dev as well.

Branches

Branches are used to separate out features and prevent changes from causing disruptions in the main branch. Some operations for branches are as follows →

- Make a new branch and switch to it →

git branch <branch_name> && git checkout <branch_name>orgit checkout -b <branch_name> - List all branches in the local repository →

git branchor include remote branches too usinggit branch -a - To delete a branch, use command →

git branch -d <branch_name>

To switch to another branch from current branch with uncommitted changes, push the changes on a stack and pop with it to get the changes back (to be done in the correct branch only) → git stash followed by git stash pop.

Merging via Pull Requests

A non-main branch can be merged into a main branch via something called a Pull Request (PR). A usual scenario is something as follows →

- A repository maintains code for a n expense tracker software with the main code within the

mainbranch - There is a feature to add budgeting as a feature in the branch

budget - When the feature set is ready, the code needs to be

mergedinto themainbranch so that users of the application can make use of it - A PR can be opened to merge the code from the

budgetbranch intomain, the easiest way being to open it from the website

[!TIP] A PR is called a “pull” request because it’s meant to signify the fact that the branch is asking

mainto pull from it!

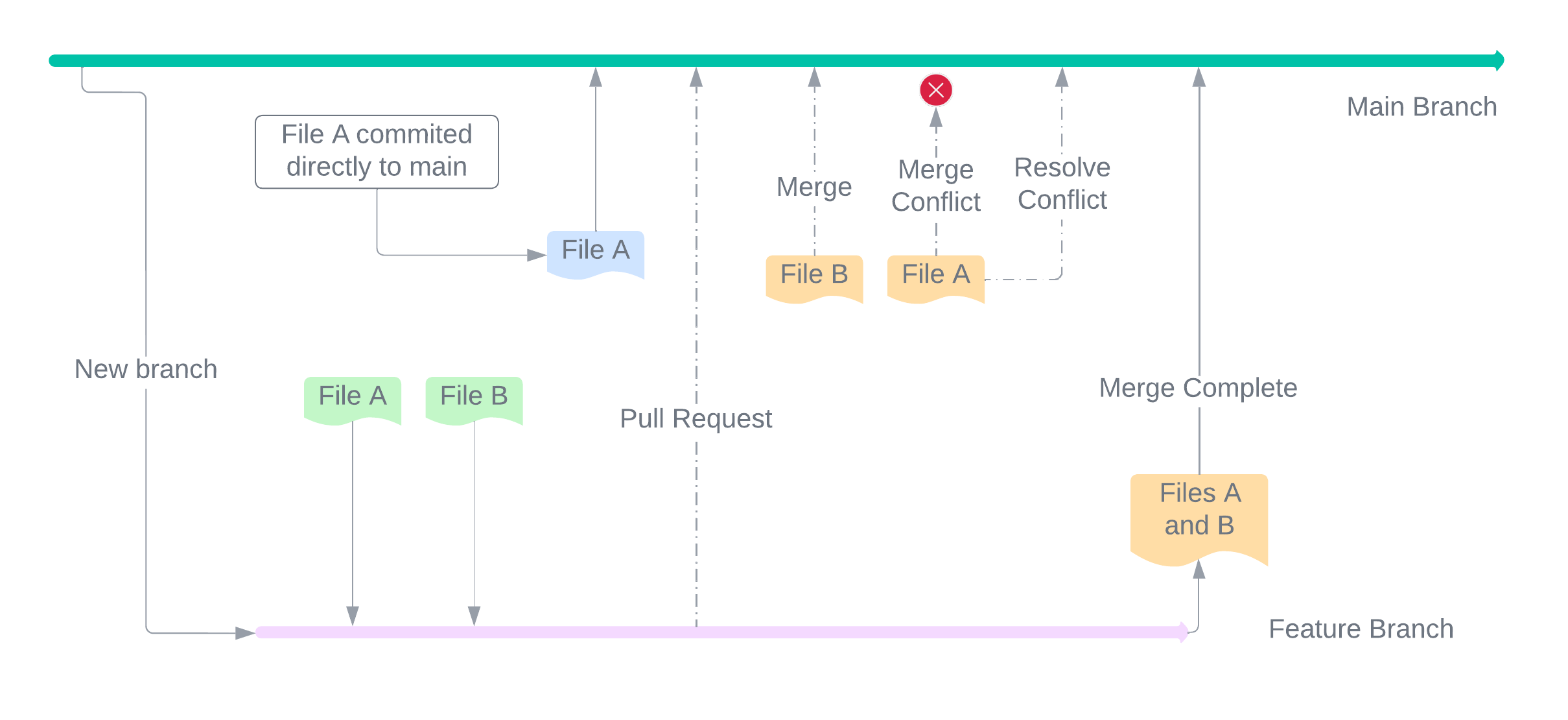

A usual problem that may arise when merging code is a Merge Conflict. Generally, when a branch is created, it is a bifurcation from the main branch with the same code. If somebody changes the code in the main branch and the same code is also modified in a branch, then a PR from that branch would result in a merge conflict because GitHub isn’t sure which version of the code is more up to date. The visual representation of PRs is as follows →

A merge conflict is represented by GitHub as follows →

<<<<<<< HEAD

conflict code

=======

branch code

>>>>>>> 445486de81907127c9f1d611ee10d90480f965e6

The =’s are a separator. The last string is the commit ID of the most recent change. To solve the merge conflict, all separators along with the non-essential code must be removed.

[!TIP] It’s always better to commit small changes to branches and build branches for smaller feature sets to avoid conflicts and difficulties in reviews.

Contributing to Other Repos

Contributing is generally the same, whether it is within a repository owned by a single person, a repository with collaboration among several people or a repository within an organization. Everything is meant to done via Pull Requests.

For contributing to a public repository, say pub_repo by maintainer pub_maintain, the following workflow is generally sufficient →

- Make a

forkof thepub_repo, which means essentially copying the code over frompub_maintain’s code storage to your own code storage. This can be done via the GUI and GitHub is generally smart enough to carry information about theupstreamorpub_repoalong with it. - At this point,

originis your own copy ofpub_repoandupstreamispub_maintain’s copy ofpub_repo. - To add a feature to

pub_repo, make the changes inoriginand then open a PR toupstream.

[!INFO]

originis technically the state in a local workstation clone whileremote originis the state on github.com. But, to abstract away the interaction between local clone and github.com, it’s easier to just refer to it asorigin.

The above workflow will open a PR from origin’s main branch to remote origin ‘s main branch. But of course, PRs can be from any branch to any other branch.

To fetch changes from the upstream, use git fetch upstream. If the clone state does not have information about upstream, add that information using → git remote add upstream <https://github.com/><user>/<repo>.git, where user should be pub_maintain.

The workflow for contribution is essentially the same when done within an organization or a group of individuals maintaining a repository, just a bit of a difference which is that it’s generally between branches like maintaining a personal repository.

PR Reviews

A really important aspect of PRs is Reviews. When contributing to a repository, specially when it’s within a group or an organization, it is important to make sure that the changes within a PR are actually intended, valid and non-breaking. So, the idea is that other maintainers, collaborators or developers possibly with higher access levels to the repository will review the changes and approve those.

GitHub can be configured to require x number of approvals before merging a PR. A reviewer can suggest changes or approve the PR. When all parties are satisfied, the PR can be merged and the new code that lands would likely not break anything.

As a bonus, if you review code, try to make suggestions using the GitHub UI’s suggestion button when adding a review comment. In MD syntax, it looks like the following →

~~~suggestion

code line(s)

~~~

This allows the other person to batch all commit suggestions into a single commit and make the changes faster rather than manually changing as per all suggestions.

CI/CD - GitHub Actions

CI/CD can be performed on a repository in GitHub using GitHub Actions. There are different requirements for running these workloads, but the free tier usually suffices for general software/code.

For example, a CI workflow can be defined by adding a yaml file to the .github/workflows directory in the root location for the repository. One such workflow from my containerized-security-toolkit repository is as follows →

name: Security Image

on:

push:

branches:

- 'main'

schedule:

- cron: '0 0 15 * *'

workflow_dispatch:

inputs:

tags:

description: 'run'

required: false

type: boolean

jobs:

docker:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v2

- name: Docker Login

uses: docker/login-action@v1.10.0

with:

username: tanq16

password: $

- name: Build and push security docker

uses: docker/build-push-action@v2

with:

context: security_docker

push: true

tags: tanq16/sec_docker:main

- The

ondefines the events which trigger the workflow. In this case, every commit on the main branch and the cron job of every 1st, 14th and 28th day of the month triggers the workflow. - The

jobsdefine the actual commands/actions that are executed in the workflow. - The

usesdefines a public action that is inherited to run in the current workflow. Alternatively, theruncan be used to define exact commands that need to be run in the CI environment. - Multiple actions/commands can be defined within the

stepsto denote the serial execution of them in the given order.

Another example of GHA in use is when GitHub Pages is enabled on a repository. Many Jekyll site generator themes also have good CI/CD workflows within their respective repositories.